Bellefontaine in the 1800s

The story of Bellefontaine Cemetery began in the early nineteenth century when an international movement began to transform burial practice in America. Up until that time, the dead had been buried in churchyards, on family property, or in small city graveyards. As cities flourished, however, the land set aside for the dead grew increasingly valuable. When developers claimed these urban graveyards for the growth of cities, those interred there had to be moved elsewhere.

The Rural Cemetery Movement

The rural cemetery movement sought to establish “cities of the dead” in park-like settings outside of urban centers so that those who had died could truly rest in peace. The rural setting also allowed visitors to reflect and remember in dignified, natural surroundings, far from the distractions of the city.

The first of the rural cemeteries, Père Lachaise Cemetery, opened outside Paris in 1804. It was the model for America’s first landscaped cemetery — Mount Auburn Cemetery, founded in 1831 in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The new cemetery movement was influenced by the romantic perception of nature, art, and national identity along with European trends in garden design.

Rural enthusiasts viewed cemeteries as canvases where moral and ethical values could be illustrated through nature. Placing graves in a garden was a major shift from the graveyards of the past. By the early nineteenth century, perceptions began to change about death and dying. No longer perceived as grotesque, but as something beautiful yet solemn, the location of a grave was both symbolic and personal. The United States was slower to adopt such ideas because Americans spent decades taming the wilderness into a productive and pastoral environment, subduing wild nature into domestication as people moved westward into undeveloped territories. Once the United States became more urban in character, the rural cemeteries were embraced as integral components of a successful nation.

St. Louis’ Population Explodes

St. Louis’ city leaders began to realize the need for a rural cemetery by the 1840s when it became clear that the city was becoming a national center of trade, industry, and commerce. When St. Louis passed its 1823 ordinance restricting burials from within its limits, the community remained relatively small. In 1830, St. Louis was ranked the 57th largest American city with 4,977 residents. By 1840, St. Louis had jumped to the nation’s 24th largest city with 16,469 residents. In 1850, St. Louis became eighth-largest city in the US, with 77,860 residents. St. Louis’ explosive growth was fueled by river trade and the city’s location near the confluence of the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. Its importance grew from a small frontier village to the “gateway of the west” within a matter of years. This was furthered by the news of Lewis and Clark’s famous expedition and return to St. Louis. Another factor in catapulting the city’s population was its appeal to immigrants, particularly Germans, who were persuaded by propaganda to settle in the “Missouri Rhineland.”

St. Louis was prompted to establish its own rural cemetery in 1849 for a number of reasons. Like other cities that embraced the rural model, St. Louis was growing by leaps and bounds. As commercial, industrial, and residential growth pushed the city’s limits westward, older burial grounds near the riverfront closed, and bodies had to be reinterred time and again. Although there were 22 cemeteries located in St. Louis in 1849, most were growing crowded with no room for expansion to accommodate the booming population. Equally troubling to the proponents of rural cemeteries was the impermanence and impersonality of these old burial places, often poorly maintained and mostly forgotten, overwhelmed by the noise and bustle of city life.

The individuals who organized and directed the new rural cemetery in St. Louis were involved in railroads, banking, and land speculation – businessmen, lawyers, politicians, and opportunists. These organizers wanted to establish a distinctive cemetery and were interested in the emerging field of professional cemetery management. During the 1840s, there was an obvious push by business leaders to bring St. Louis into the national limelight as a city that provided opportunities equivalent or superior to those in large northeastern cities such as Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Bellefontaine’s organizers shared this attitude and wished to create a premier cemetery in St. Louis that was comparable to those in Boston (Mt. Auburn), New York (Green-Wood), and Philadelphia (Laurel Hill).

Bellefontaine’s founders hoped that the cemetery would become a major civic, cultural, and historical institution — a “community classroom.” Visitors walking through the cemetery — especially newly arrived Irish and German immigrants — were meant to be inspired by the examples of notable St. Louisans, bolstering a sense of community and civic identity for their adopted home. The cemetery was also to be a showcase for fine art, architecture, and horticulture. The cemetery’s embrace of immigrants, different religious denominations, and later, its accessibility by streetcar for middle and lower class patrons, made Bellefontaine an inclusive institution for the times.

St. Louis was hit by the cholera epidemic in June of 1849, creating an even greater crisis as the death toll rose and land for burials diminished. The city’s rural cemetery, established just prior to the epidemic, could not have been timed more appropriately. By the early part of July, the epidemic had so alarmed the community that everyone who was financially able to do so, except the mayor, fled from St. Louis with their families. By the end of August, a whopping 4,317 people — nearly seven percent of the city’s population — had perished.

Like other rural American cemeteries that preceded it, Bellefontaine was planned well beyond the borders of the city’s residential population. Under Bellefontaine’s 1849 rules of incorporation, the cemetery was to be situated “not less than two miles, nor more than five miles distant from the present corporate limits of the city of St. Louis.” There were two reasons for the distanced location – the first had to do with rising real estate values and diminishing vacant land in downtown St. Louis suitable for a large public burial site. The second reason relates to health concerns. During the mid-to-late nineteenth century, it was a commonly held belief that diseases were spread not only through the living, but also the dead. Like many American cities, St. Louis held such concerns, particularly considering the fact that the city was hit by cholera the same year that Bellefontaine incorporated.

Led by banker William McPherson, the Trustees of the Association purchased 138 acres north of the city, including the Hempstead family farm with its family graveyard. With graves dating back to 1817, this is the oldest lot in the cemetery. Over the next 22 years, the cemetery would purchase additional land, including a part of John O’Fallon’s estate, which today totals 314 acres. With its incorporation, Bellefontaine Cemetery became the first rural cemetery west of the Mississippi.

Almerin Hotchkiss Arrives

On July 23, 1849, the Missouri Republican reported that the cemetery had acquired “a gentleman from the East, who has had several years’ experience in laying out and improving cemetery grounds.” Bellefontaine’s new grounds superintendent, Almerin Hotchkiss, arrived in early October of 1849. The 33-year-old Hotchkiss had been working at the well-regarded Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn, New York. He was an early landscape architect – then called a landscape gardener – who designed in the style that would come to be associated with men such as Frederick Law Olmstead and Maximillian Kern, who designed Forest Park in St. Louis. Hotchkiss also designed Chippiannock Cemetery in Illinois and the suburb of Lake Forest outside of Chicago.

Upon arrival in St. Louis, Hotchkiss immediately began directing a group of men (between 15-28 individuals, depending on the task) who assisted with clearing undergrowth, plowing and grading the property, constructing roads, and planting trees. Within his first year at Bellefontaine, Hotchkiss and his assistants improved more than 100 acres, constructed “a substantial picket fence, eight feet high,” and started constructing a receiving tomb. Additionally, the workmen erected a temporary gate, constructed an office for Hotchkiss, and built two stone cottages for the keeper and porter. Hotchkiss would spend the next 46 years of his life improving the cemetery grounds.

On May 15, 1850, St. Louis dedicated its new rural cemetery, which had been appropriately renamed as the Bellefontaine Cemetery Association two months earlier. The change in name related both to the former military post (Fort Bellefontaine) and the route (Bellefontaine Road) bordering the cemetery’s eastern perimeter. The dedication ceremonies received extensive coverage in the city newspapers. In his dedication speech, the Rev. Truman Marcellus Post called the cemetery “the shadow, the counterpart” of the city. Junior Editor of the St. Louis Intelligencer, A.S. Mitchell, Esq. attended the dedication and made the following observation.

The location of the Cemetery grounds is beautiful, in the extreme. They afford scope for every variety and extent of improvement and decoration. They lie about five miles north of the Court House, and embrace about one hundred and thirty-eight acres. The drive to the Cemetery will ultimately be one of the most interesting leading from the City. The projected improvements of the grounds are extensive, and in admirable taste. The miles of avenues, walks and ways, through the grounds, leading across plateaus, and over hills, and through embowered dales, and presenting every conceivable view and aspect of beauty of which the grounds are susceptible, will yet preserve a simplicity of arrangement and symmetry of design, that will ever charm the appreciating visitor.

At the time of the dedication, approximately half of the cemetery’s grounds had been laid out in meandering roads, footpaths, and trees. The primary road, which had come to be called the “Tour,” totaled four miles in length. The Tour had a generous width of 20 feet with eight-foot borders on each side. All lots were to front either a road or a path, allowing carriage access to individual lots, and every lot and road was to be laid out with borders that (if owners preferred) could be “ornamented with flowers and shrubbery [to] add beauty to the place.” Hotchkiss employed the standard features of rural cemetery design with curvilinear roads, planned vistas, lakes, and a prominent entrance.

Natural landscape features such as hills, valleys, and glens, were retained, with roads and family lots following the land’s topography. Trees and underbrush were cleared to provide views from the roads to family lots. After trees were removed, additional trees were planted along the property’s perimeter to frame views and align the roads. Mature trees, many over a century old, remain one of the landscape’s main features today. Many existing trees predate the cemetery, while others are from the efforts of planting that spanned many decades. The cemetery’s estimated 5,000 trees provide a forested canopy shading the grave sections. Many trees are Missouri natives, but there are also exotic species from around the globe, selected for their aesthetic interest such as flowers, fall color, or form.

The Civil War did little to impede daily routines at Bellefontaine. During the early 1860s, Hotchkiss began to introduce non-traditional plantings to the site, including white pine, Norway spruce, balsam, ash-leaf maple, and “myrtle for graves” – a practice common in the late 1800s, but relatively novel in the 1860s.

Post-Civil War Bellefontaine

After the Civil War, a number of physical changes occurred at Bellefontaine. One of the most significant was the 1878 completion of the Amaranth Gate, located near the southeastern corner of the property. This came on the heels of the city’s completion of Kingshighway’s northern sector in 1877, a major thoroughfare terminating near Bellefontaine’s Willow Gate on West Florissant Avenue. Other improvements in the 1870s included the addition of drinking fountains, new fences, new plantings, and road improvements. By the 1870s, Bellefontaine began using its former agricultural grounds for burials, and by the end of the century, there were over 1,000 interments a year. Large family tombs were constructed along the river bluffs on Prospect Avenue, many of them both beautiful and architecturally significant.

The Landscape-Lawn Cemetery Design Movement

Nearly 50 years after its founding, Bellefontaine was inspired to modernize. Spring Grove Cemetery in Cincinnati and the burgeoning landscape-lawn cemetery design movement ushered in a new aesthetic that replaced ornate and elaborate Victorian fences and hedges with open, cross-lawn views. Bellefontaine followed suit by removing hedges, fences, elaborate plantings, and stone copings. Open, cross-lawn views became the more common aesthetic of the cemetery, bringing Bellefontaine in line with modern ideas about cemetery design. The changes also made Bellefontaine appear more open and park-like, creating a more integrated landscape composition than the earlier delineation of individual lots with distinctly defined spaces.

Bellefontaine in the 1900s

In 1901, the city proposed the construction of two “asphaltum boulevards” that would make the cemetery more easily accessible. As the St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported at the time, “the journey to Bellefontaine and Calvary cemeteries from the city [was] long and by unimproved ways. There [were] no pavements. There [was] mud in winter and spring and dust in the summer and fall.” The paper estimated that 600,000 people visited the two cemeteries each year.

To serve its families better, the cemetery converted the gravel roads to macadam, making the cemetery very popular with “wheelmen” and their large three-wheeled bicycles. In 1908, after repeated inquiries from the St. Louis Automobile Club, the association reluctantly agreed to permit lot owners restricted access “in their machines, if they desire.” The cemetery’s rules were adjusted accordingly over the ensuing years. Initially, Bellefontaine only allowed automobiles access one day per week, and only for lot owners. A five-mile-per-hour speed limit was imposed and vehicles “driven by women or children” were forbidden. Three years later, the cemetery loosened its regulations, allowing “automobile” funerals . . . “including automobile hearses” In the five years that followed, many additional restrictions on automobile traffic were removed to accommodate changing times.

In 1904 – the year that St. Louis hosted its own World’s Fair – Bellefontaine erected what would be its most visited memorial to date, an obelisk and bust commemorating General William Clark (1770 – 1838). Unlike Mt. Auburn, which hosted thousands of visitors per year and encouraged “genteel recreation,” Bellefontaine did not encourage visitors to use the site for public outings. Although carriage excursions along the cemetery’s Tour were permitted during the mid-to-late nineteenth century, this was no longer the case when automobiles began to enter the grounds. Bellefontaine’s revised regulations in 1909 allowed “no dogs; no bicycling, fishing in lakes, or skating.” Despite the strict regulations, many took advantage of the cemetery’s recreational potential as noted in a St. Louis Post-Dispatch article from 1895, which reported “fearless skaters” using the ponds at both Bellefontaine and Cavalry cemeteries when “superintendents” were “not so careful after night-fall, especially on cold evenings.” Things loosened up slightly after 1910 “largely because of the hospitality of Mrs. Francis G. Burgess, wife of the assistant superintendent of interments” and Bellefontaine began hosting neighborhood picnics and church socials.

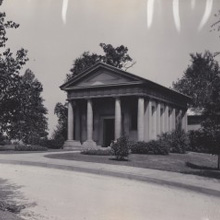

The cemetery’s landscape underwent a transformation after 1900. In 1902, Eames & Young designed a new receiving tomb and chapel. These were constructed between 1908 and 1909 “overlooking the Mississippi River and Chain of Rocks.” Building projects continued through the 1920s with the addition of stone walls, wrought iron fencing, and a new office building, comfort station, and gatehouse located near the Willow entrance off of West Florissant Avenue. Today, Bellefontaine’s appearance is largely reflective of the improvements made during the 1920s and 1930s, including stone walls surrounding the cemetery, stone and iron gates, and the office, which is still in use today.

With the onset of the Great Depression, lot sales slowed, and in 1931, the cemetery’s expenses exceeded its income for the first time. Within two years, finances had rebounded and the cemetery continued to make improvements to the grounds. The hardship of these years further impressed upon trustees the importance of an endowment, and ever since, financial stewardship has remained a core focus of the Cemetery Association.

By the 1990s Bellefontaine was thriving, but much of St. Louis’ population had moved west, sending many urban neighborhoods into decline. The Cemetery Association began working to cultivate community development, along with partners including Habitat for Humanity, New Sunny Mount Baptist Church, and the cemetery’s affiliate, Union West Florissant Development Corporation. These partnerships have yielded hundreds of rebuilt homes, grants to community groups, and ongoing planning to bring jobs and services to the neighborhood. Commitment to its community is an important part of Bellefontaine Cemetery’s mission.

Bellefontaine Today

The beginning of the twenty-first century brought renewed invigoration to the cemetery. The Hotchkiss Chapel was renovated in 2010, converting the unused receiving tomb in the rear to an indoor columbarium and carefully restoring the chapel. An outdoor columbarium was constructed between Cascade and Cypress Lakes on the western side of the cemetery. The Cemetery Association completed a Master Plan in 2012 to ensure that Bellefontaine would remain one of the premier cemeteries in the country. The plan addresses the best future uses for undeveloped land and serves as a guide to preserving, protecting, and enhancing the historic landscape. In order to honor and recognize the vast collection of trees in the cemetery, Bellefontaine became a recognized certified Level II arboretum. The mission of the arboretum is to enhance the cemetery by increasing tree species diversity, providing critical habitat for birds and small mammals, and providing an urban oasis for the community.

In spite of many changes, the cemetery continues to reflect the original design of Almerin Hotchkiss. While the cemetery’s 138 acres have grown to 314, Bellefontaine’s fourteen miles of curved roadways still afford beautiful views of the landscape, including thousands of shrubs and trees and hundreds of works of art. Bellefontaine has become an outdoor museum, containing fine sculptures and memorial art reflecting the changing tastes of our culture.

With 87,000 interments, Bellefontaine is the final resting place of men and women whose lives have contributed significantly to the westward expansion of our country. A visit to their graves provides a keener appreciation of our national heritage by connecting past, present, and future generations.

Read more about the rich history of those residing at Bellefontaine Cemetery in Movers and Shakers, Scalawags and Suffragettes: Tales from Bellefontaine Cemetery by Carol Ferring Shepley.